Architecture

Architecture

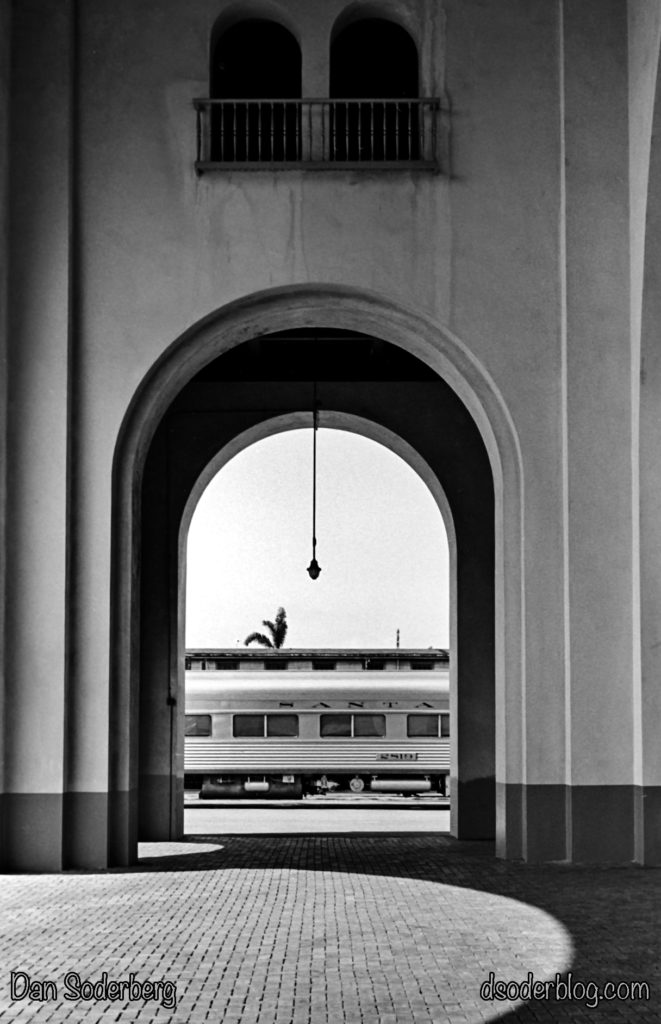

Kelso, Luck Of The Draw

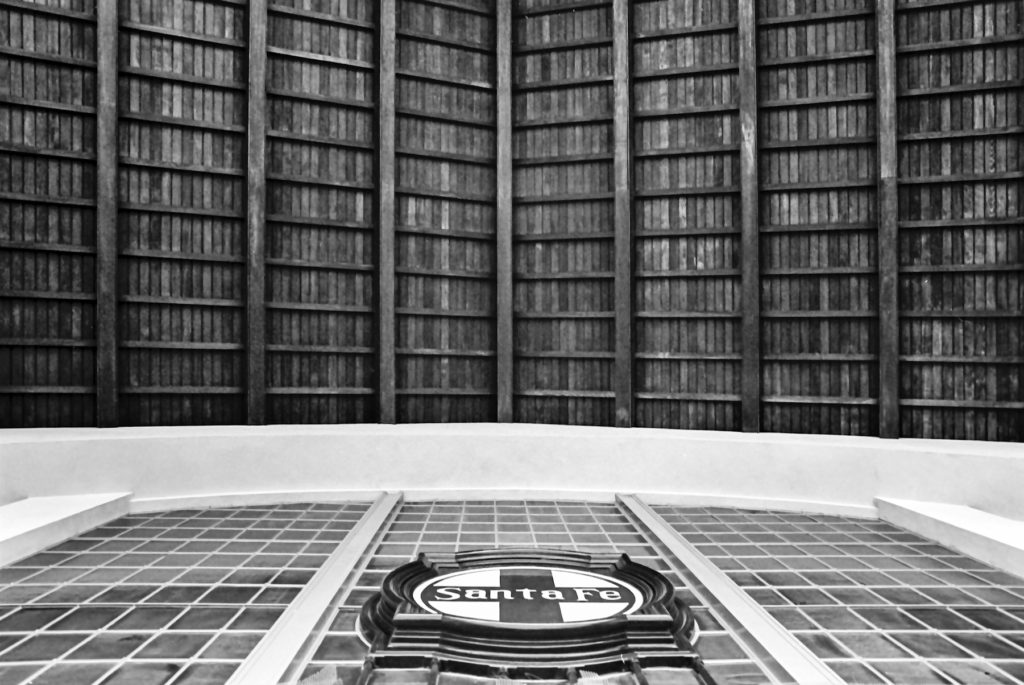

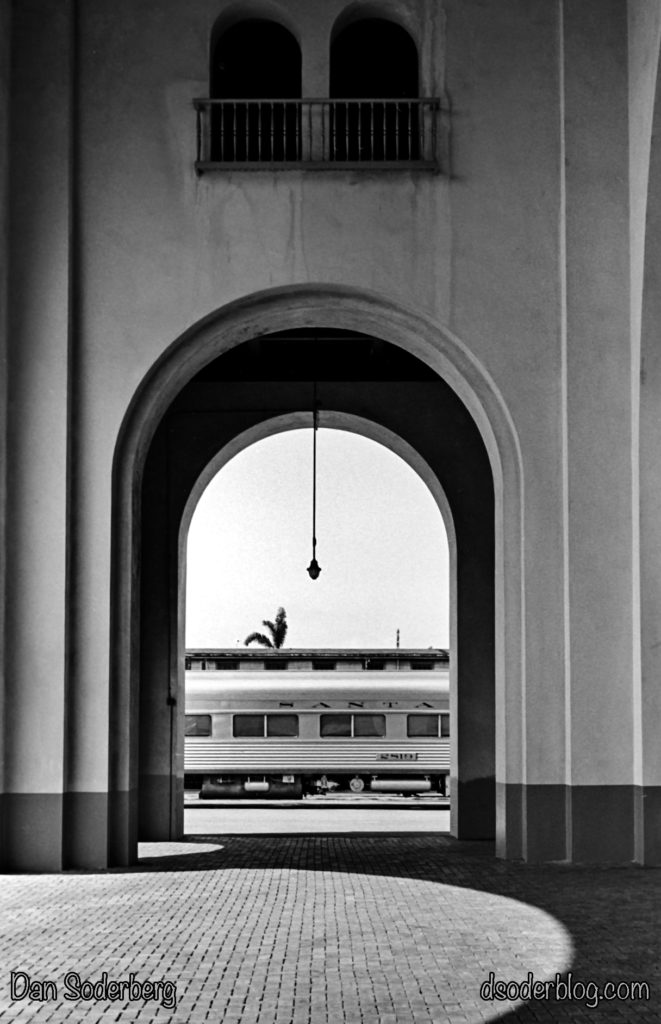

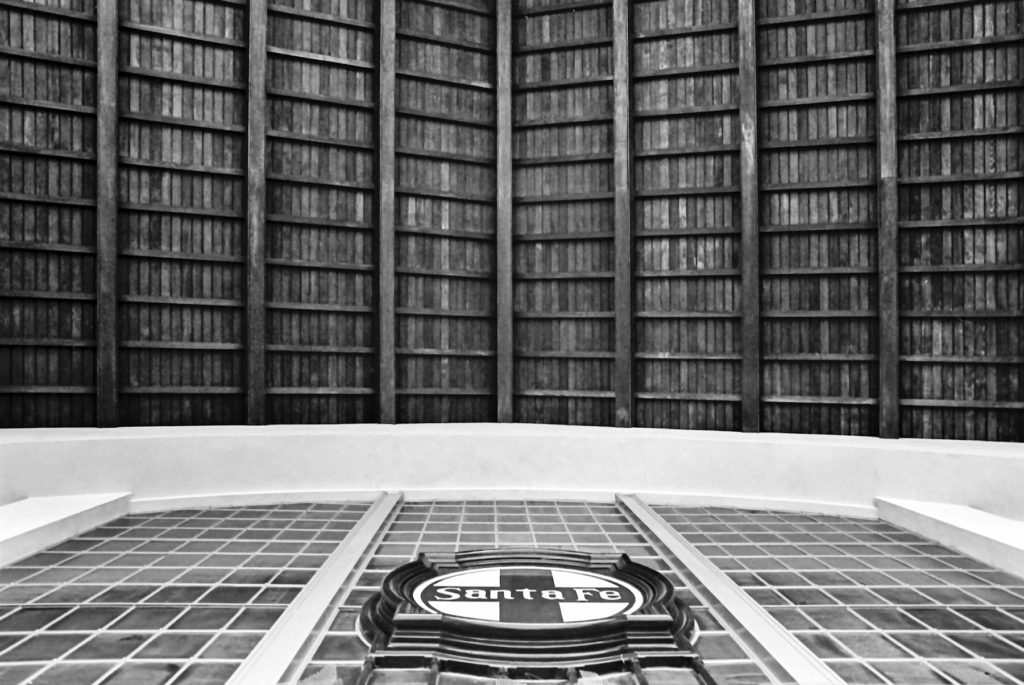

Seemingly out in the middle of “nowhere” along Cima Road in the Mojave Desert, this jewel of a train station suddenly appears as a desert oasis. It’s the 1923 Kelso Train Station. Unlike the ghost town relics surrounding it, this beautiful building is in nearly pristine condition.

While the station is from 1923 the importance of the site as a railroad rest stop goes back to at least 1905 when Kelso was founded. The name was chosen purely by chance. Name rights were submitted on pieces of paper and placed into a hat. Upon draw, all at once John H. Kelso had a town named after him.

This Mission Revival and Spanish Colonial Revival design comes from the drawing boards of John and Donald Parkinson. If you don’t know their names, you certainly know their portfolio. They designed the USC Master Plan, LA Coliseum, LA City Hall, Bullocks Wilshire, Union Station, and Grand Central Market – to name a few.

The train station survives today by the sheer will of concerned citizens who stepped up to save the building from demolition when it closed as a train station in 1985. Key to this preservation effort was The National Park Service gaining control of the site in 1994 .

The building reopened to the public in 2005 as the visitor center for the Mojave National Preserve. There are interpretive displays, both inside and out, providing a valuable understanding to the historical significance of the station’s location.

It is explained why a fancy train station is in the middle of “nowhere.” One reason is an abundant supply of ground water for steam engines.

It was a “helper” station. Because of the severity of the long steep Cima Grade, helper engines were needed to assist trains on that grade. Kelso was home of those helper engines, and there was a big roundhouse there to direct, turn around, and utilize them. Kelso was the helper station in regards to fuel and water as well.

A beautifully designed building that was well used and well loved for a long time. It became affectionately known as the Kelso Club House. More than a train and ticket station it was telegraph office, restaurant, reading room, and dormitory rooms for railroad employees.

The interior has been restored and preserved as well, including the lunch room. Nice they didn’t forget to save the neon sign. However it appears it has suffered some wind damage, as the power cable was pulled out of the wall.

The focus of my photo essay is the exterior. Visitors wanting to see the Kelso Train Station inside and out – be advised they are closed Tuesdays and Wednesdays.

In addition to the historic translation, visitors may also view the Kelso Jail. These human cages were utilized from the mid 1940’s all the way to 1985. To lock up, for a night or two, the town drunks who became unruly. Neither the heat or the cold of the Mojave made these cages very comfortable.

But by all accounts, this sort of imprisonment hasn’t gone away. Only from here.

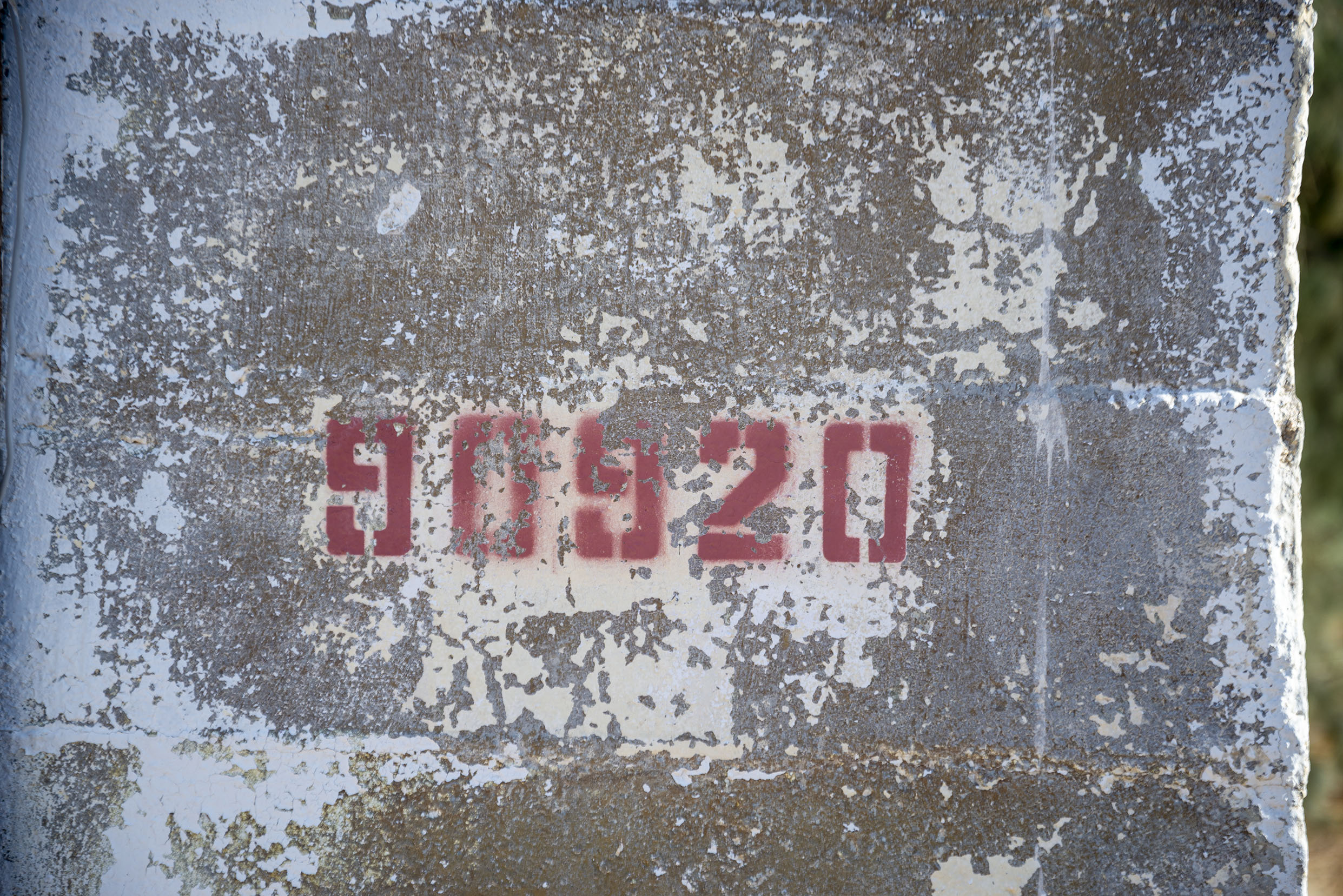

You know you’re in downtown Kelso when…you see the Post Office. Open from 1905, through Kelso’s boom years during WW2, and finally closing in 1962.

Ghost Town…ghost sign.

Kelso 90920

Foundation and Fireplace, Kelso Ghost Town

The warmth and comfort once provided, now a ghost town ruin.