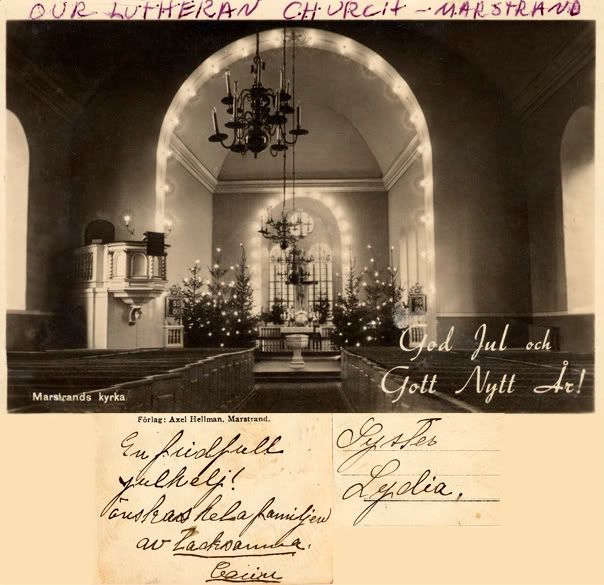

It was customary in Sweden for the Christmas tree to remain up until January 20. Then to have friends over to sing and dance around the tree. “Mama served our favorite kinds of food.” Greta was still busy eating the candy ornaments.

“It has not been this cold in 50 years,” wrote Gunhild. “You can only be outside for about 30 minutes or your face feels like it will crack.” Keith sent them an electric heater he bought at Thrifty’s for $0.98 cents. And a small radio for $9.98. The cheapest radio available in Sweden cost $75.00.

The heater was put to use promptly. Before, their room at night was so cold they used every blanket in the house. Still they shivered. Hot water bottles were useless as they cooled quickly. Then it was too cold to get up and fix new ones.

“In the morning we were tired from the weight of blankets on our bodies.”

They listened to the new radio a lot. Besides Swedish radio Germany, Russia and England came in. Russia offered mainly church and prayer programs. From Germany it was all “marches and noise.”

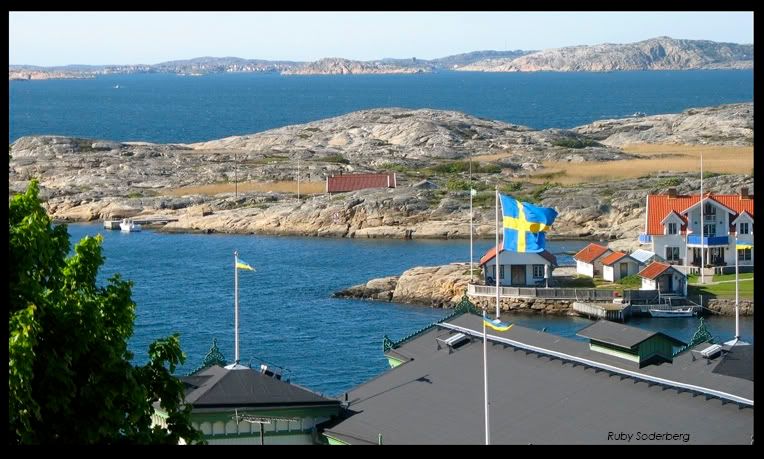

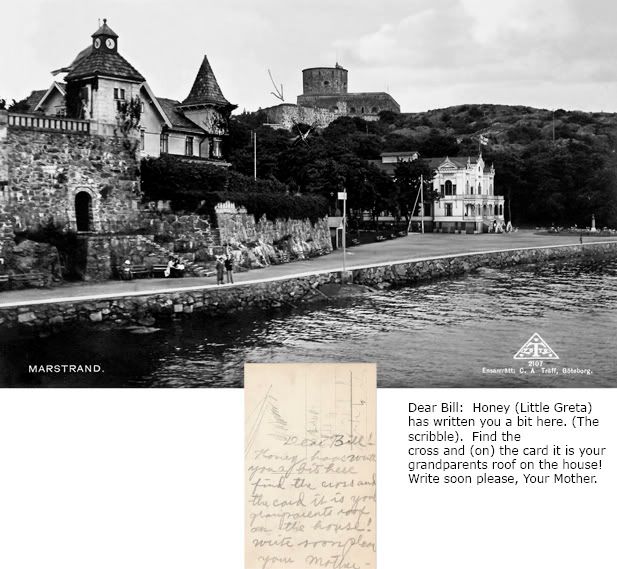

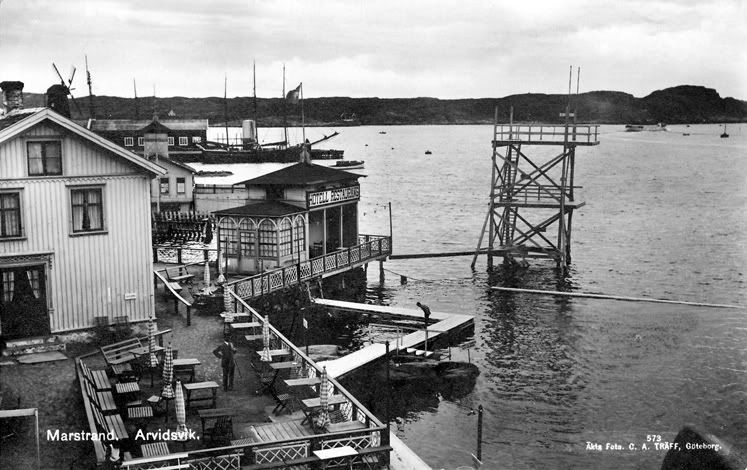

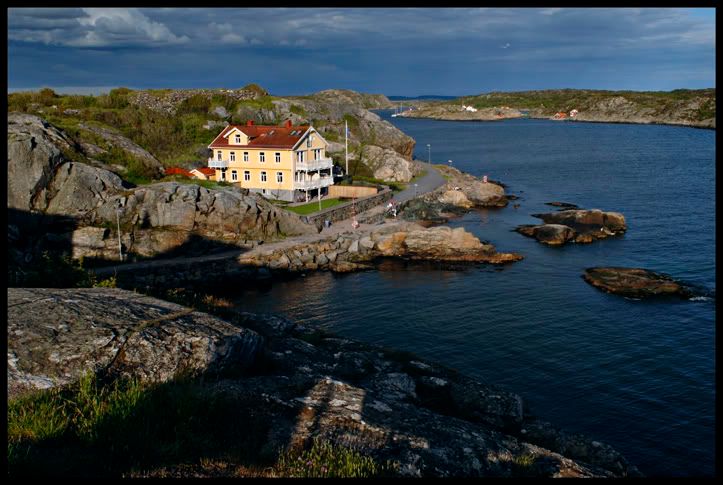

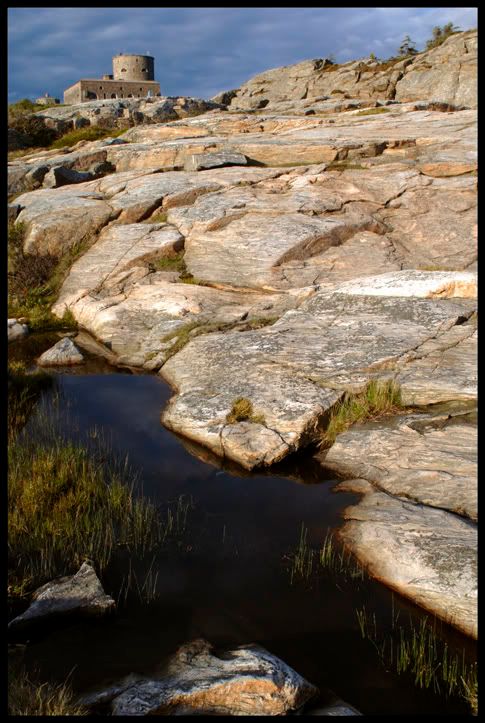

Marstrand was solidly frozen in. Arrival and departure of goods and services came by horses and sleds. People traveled to and from Marstrand and Göteborg on ice skates. By Greta’s 6th birthday in February she handled both skis and skates competently.

Since November Sweden’s neighbor to the north, Finland, was at war with invading Soviet Union. Stalin and his generals had not anticipated the fight on their hands. Although Sweden and Finland had strong ties, Sweden did not veer from their strict neutral policy. Assistance was not provided. She did however nurture a citizen’s volunteer effort for Finland. At least 10,000 Swedes felt compelled to join Finnish forces.

Besides volunteering for The Red Cross, Gunhild was among the many women working for the Finnish cause by knitting. About the fight in Finland “They are the good guys; our heroes.” She thought if the Finns made it, Russia would leave Sweden alone.

There was wisdom in that thought. Sweden carefully and alertly positioned herself to be the worst possible headache for any invading nation by diligently building up the strongest defenses of all Scandinavian nations. That Finland proved to be a bitter pill for Stalin was noted by the world. Sweden was prepared to be a whole lot more trouble.

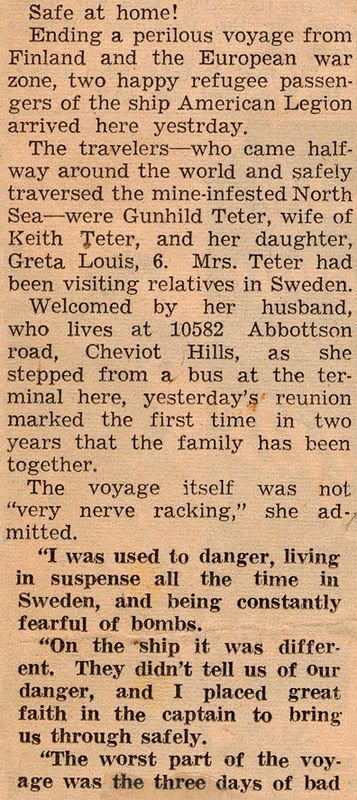

“They are now torpedoing and sinking almost all ships that venture into this area,” wrote Gunhild. People commented among themselves “If its not the torpedoes that get them, then the icebergs will.”

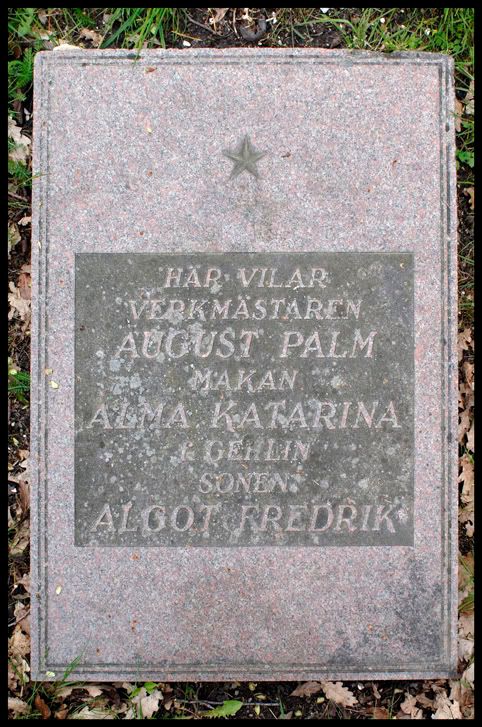

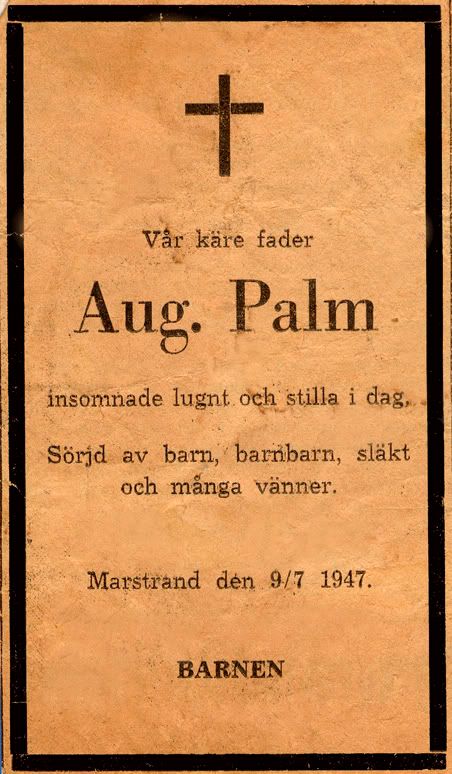

A war time atmosphere wasn’t helping Grandfather August. He was laid up and lame for over two weeks by another “mild” stroke. He didn’t look well as Gunhild helped with his shoes and socks every morning.

Still, their suitcases were packed and ready. But with month after month passing in wait, the cases had to be packed and repacked according to seasonal needs.

Stateside Keith was busy locating an available liner. In April 1940 he reserved one. He forwarded tickets to Gunhild along with $40.00 in cash. She was desperate to get $75. Food alone cost $35; other expenses seemed inevitable. All funds at this point were borrowed. Undoubtedly, Keith tapped every resource he knew.

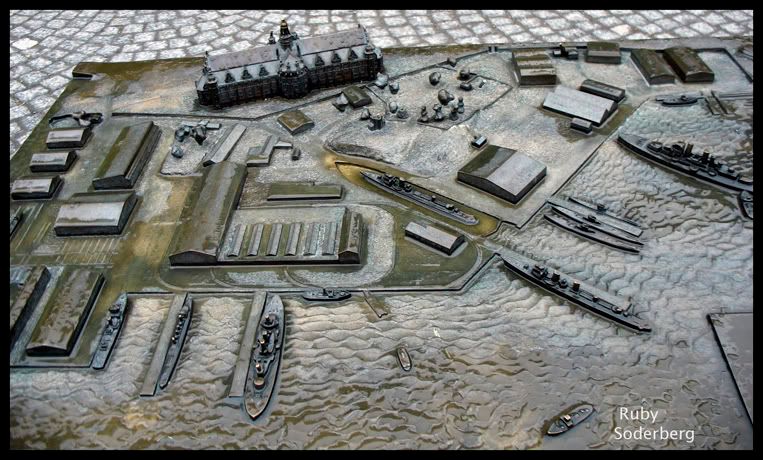

Hitler had other ideas about ship traffic. On April 9th Germany invaded Denmark and Norway. A naval blockade was in effect. Göteborg was a port that lay motionless with a glut of docked ships.

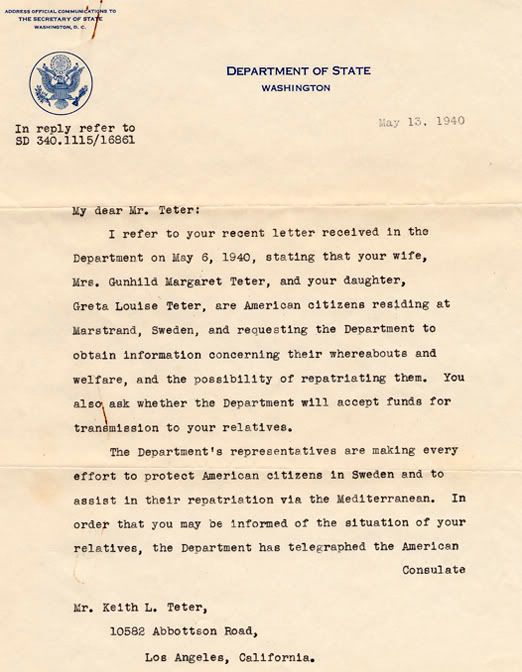

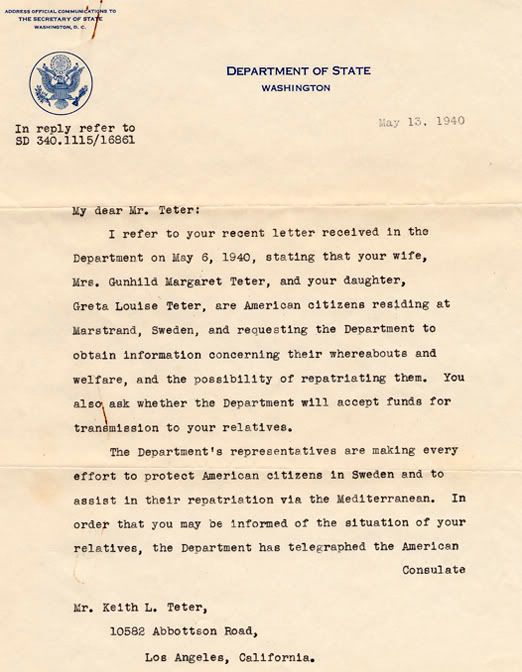

There was a complete break in communications. Keith wasn’t sure if Gunhild departed or not. With no idea where his family was or what happened to them, he contacted the U.S. State department.

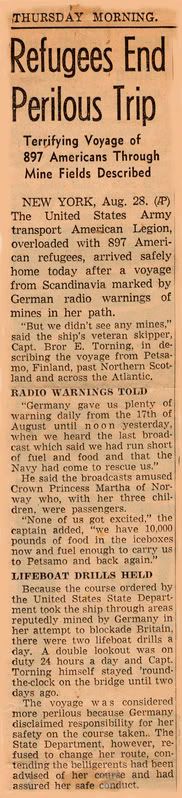

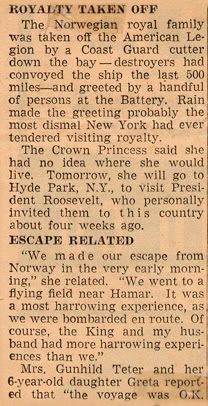

The federal government took up the job of repatriating the many U.S. citizens caught in the war. This project partly came under the hand of President Franklin D. Roosevelt when he offered safe harbor to Norway’s Royal Family. The ship assigned for that mission may well have been the last chance out.

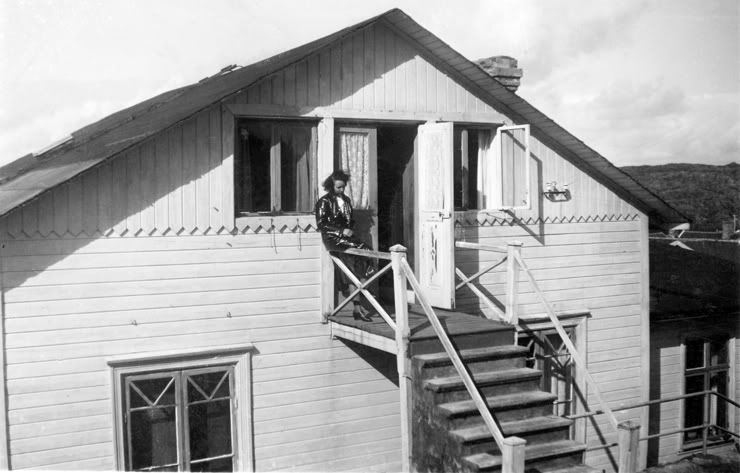

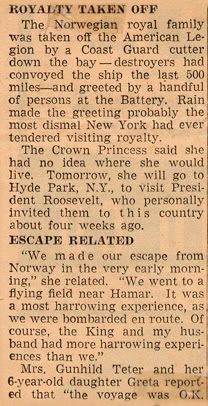

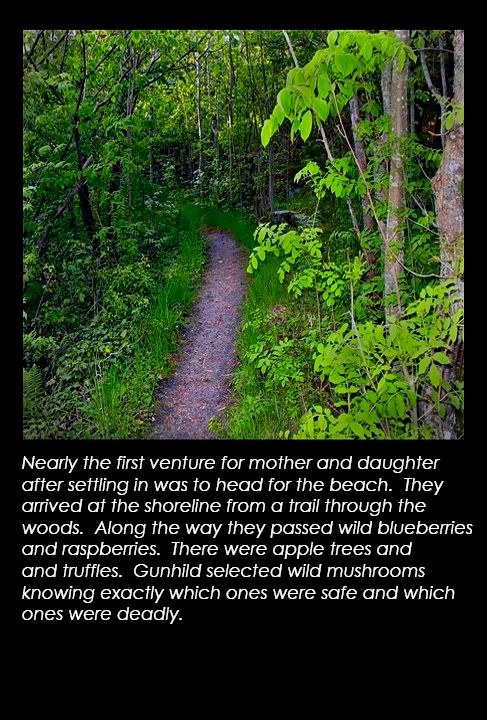

“One very early morning in July, (it was still dark) two men came quietly to our house and rapped softly on the door. Mama, who wasn’t sleeping well, heard the knock first. Throwing on her bathrobe, she hurried to the door and carefully peeked out. A man’s deep voice cautioned us to be very quiet and not to turn on any lights. We were to dress quickly and come with them as soon as possible. ‘Take only the barest of necessities,” the other man advised us. We had already said most of our goodbyes to Grandfather in the last several weeks. We were very sad he refused to come with us. No amount of cajoling would change his mind. ‘I am too old,’ he told us. ‘I must stay with my country.’ He knew we would be leaving at a moment’s notice any day. I was wearing a gold cross he had just given me and I dressed very quickly by myself. I put on a new pair of rainbow-colored canvas shoes with a small buckle on the side. I had some trouble snapping the buckle as they were still stiff and new. (Mama let me choose them myself in a weak moment). We were only allowed to carry the small valises we had packed earlier containing underwear, a nightgown, a couple of changes of clothes and toiletries. Mama cut out of its frame a canvas painting of some fishing boats that a friend, Ingeborg, had painted. She rolled it up and tied it under my coat around my waist to take with us.”

“It seemed forever, but in reality it was only a matter of minutes and we were ready to depart. We hastily kissed Grandfather August goodbye one last time. With tears in our eyes we turned to go. Mama knew she would never see her father again.

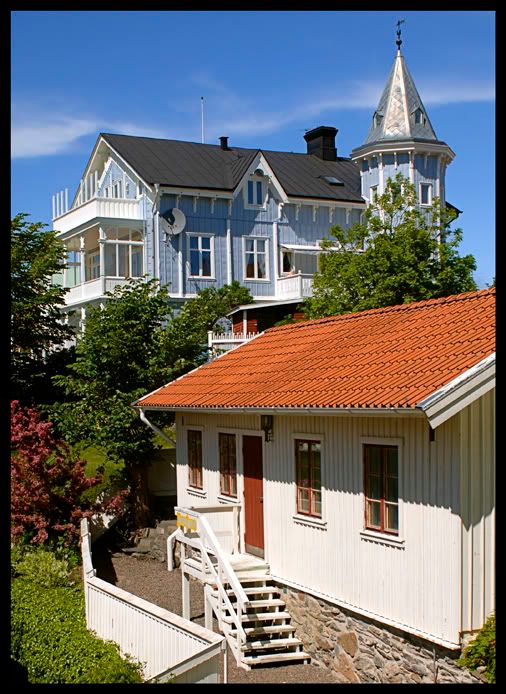

“The two men escorted us to the water in the dark. A small row boat was tied to the wharf. We climbed aboard with one of the men. He rowed us across the water toward the other side of the bay. We turned around to see our home on the hill where we had lived for the last two years and thinking about Grandfather inside. I wondered if he was looking out the window for us as we rowed.”

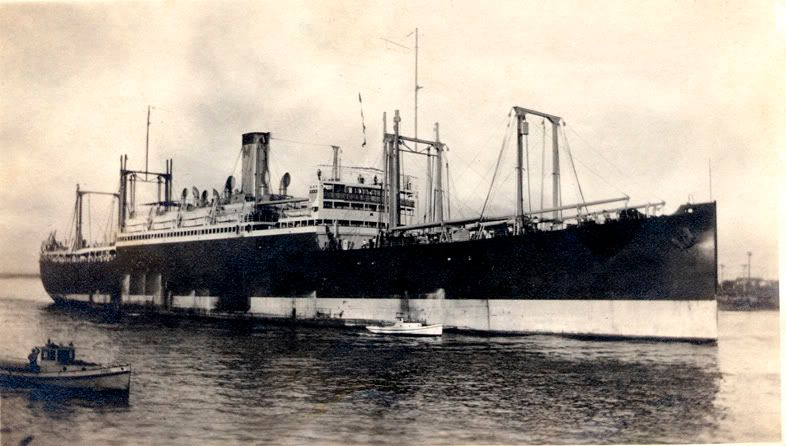

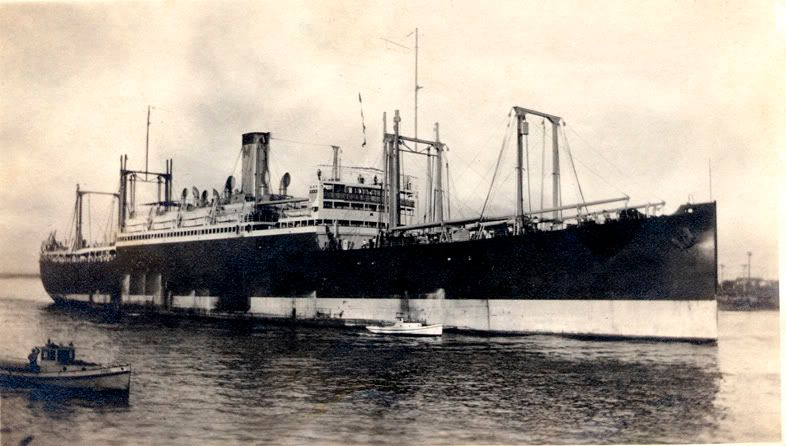

The plan was to reach the port of Petsamo, Finland, which was still open to neutral passage. The U.S. army ship American Legion awaited the refugees. But the trip there was difficult and dangerous. It was made mostly under the cover of darkness through the war zone. Secrecy and quiet was the utmost of importance.

“We took at least two small boats, a train, and a small bus. From the bus I remember seeing small burned and smoldering villages or towns. Bodies of people and animals were here and there. Some were burned. Some just lying on the cold ground. Mama told me not to look but I peeked anyway. At times we traveled at night on a bus or train. Other times we spent safely away in caves or underground passages. We had to sleep sitting up because the quarters were so small and cramped. There must have been fifteen or twenty of us fleeing. There were various nationalities, adults, and children. It was imperative the children not squeal, cry or make noise of any kind whatsoever. I slept with my head in Mama’s lap. I don’t think she slept much at all during this trip.

“At our final stop on land which was along the shore line, we had to wait a couple of days for our ‘connection’ to Petsamo.

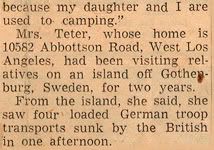

“While waiting we saw four German troop transport ships sunk by the British.

“Every morning I had trouble buckling my beautiful new shoes. First because they were new. Secondly because I slept in such a cramped position my feet were swollen. When the day finally came and we had to move quickly so as not to be discovered, I was not able to fasten one shoe. Everyone was standing and having to wait as I struggled with my shoe. ‘Just leave her here!’ a grumpy man growled. Mama grabbed me by the arm and pushed me onto the bus. I held my shoe on by my toes and clumped along.

“We arrived at a tiny fishing boat. It was a long way down below the wharf. We had to descend on a tall rickety old wooden ladder. Most of the children were small enough to be carried, but I had to climb down by myself. The rungs of the ladder were very far apart for my little legs to reach. I didn’t dare whimper, but I was afraid I might fall into the ocean and they would leave without me.

“Mama was on board before me and was reaching up to help when suddenly my shoe went tumbling into the ocean. I wanted to cry, but I didn’t dare make a sound. I bit my lip and continued down the ladder and into Mama’s arms. “Don’t cry, she said, “We will find you other pretty shoes in America.”

“It didn’t take us long to reach the army transport ship American Legion.”

If Hitler only knew. Hidden on board the American Legion, Sweden sent along a 40mm Bofors anti-aircraft gun mounting which became the prototype for thousands of such guns built for the U.S. Navy during World War II.

From the time Gunhild first had obtained passage to this moment this short list of events transpired.

May 15, Holland surrendered to Germany. May 28, Belgium surrendered to Germany. June 3rd, Norway surrendered to Germany. June 14, German troops marched through Paris.

“I don’t remember exactly when we set sail for America, but it was few days after July 28, 1940.”

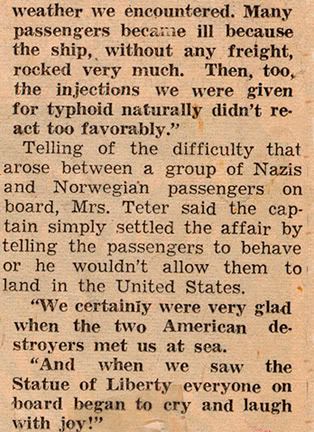

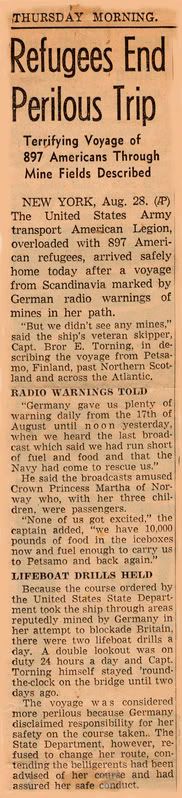

By August 8th, the Battle for Britain began. This meant The American Legion was headed though areas mined by Germany in her blockade of Britain. The U.S. was still a declared neutral and expected safe passage under international rules. But Hitler repeatedly demonstrated his regard for international law long ago. This was at best a risky voyage.

Norway’s Crown Princess Martha’s children were among the playmates Greta encountered on board. “I was permitted to play with the young prince from time to time. I believe he was a year younger than I.”

“There were many people on board fleeing Europe. About 897 of them were American citizens. There were no more children’s life jackets so mine was adult size. It hung down nearly to my ankles. It was overcrowded with people. Some had to share beds. Mama and I were fortunate. We had our own room with bunk beds. I slept on top and when the ocean became rough, I usually awoke on the floor the next morning.

“We had to attend life boat drills twice a day. A double lookout was on duty 24 hours a day and the captain himself spent many a 24 hour stint on bridge until we passed the mine fields. We had lessons in “plane spotting,” identifying the various insignias on the planes which were constantly flying over us. When we saw an enemy plane we were told to fall flat on the deck where ever we were. The children became very adept at it and it became a game to see who could go down the fastest.

“The Germans radioed continuous mine warnings. Then some really bad weather lasted 3 days. Since we had limited freight, the ship bobbed up and down like a cork. I remember seeing huge walls of water taller than the ship on each side of us as we dropped down only to suddenly shoot back up again. Many people were seasick. The infirmary was so crowded there were often two people in a bed. We all had typhoid injections which also made people sick. Mama was one of them. She was in the infirmary for many days. I believed she didn’t care one way or another if she lived or died. She hardly responded when I came to visit. I wandered the ship alone for several days exploring here and there. One day a black man who worked in the kitchen saw me wandering around inquired what I was doing there all alone. I told him about my mother being ill. He asked me if I had been eating regularly, which I hadn’t. I told him I had eaten some peanuts earlier but that was all. Every day until Mama was well, he searched me out and brought food.

An incident arose on board that perhaps predicted the scene in Humphrey Bogart’s Casablanca where groups of German soldiers singing were drowned out by French voices at Rick’s Cafe. “A group of Nazis and Norwegians on board got into a heated situation which was skillfully handled by Captain Torning. He simply told them to behave or he wouldn’t allow them to land in the United States.”

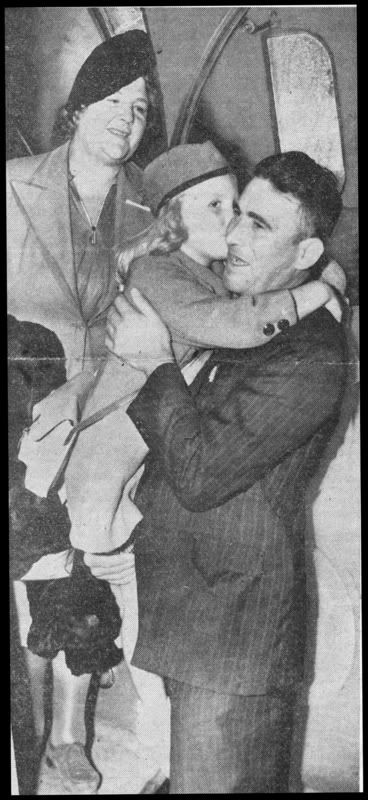

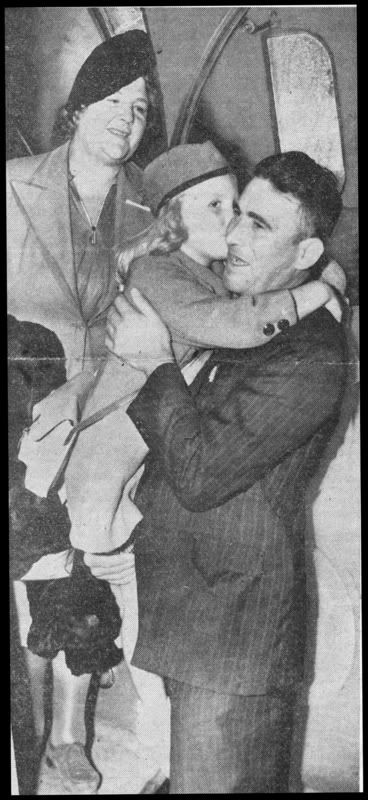

It was raining that day of August 28, 1940 as the American Legion entered New York harbor. “When people saw the Statue of Liberty they came out on deck to cry and laugh, and to cry and laugh some more. A record of the Star Spangled Banner was played; all the Americans began to sing. As we walked down the gangplank and went ashore, hundreds of passengers got on their knees to kiss the ground.”

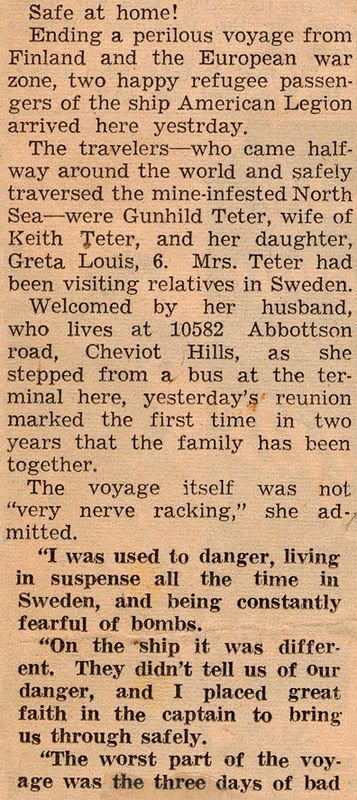

“Home at Last! Mama continued being interviewed by various newspapers for days after.

“I had to relearn English. I couldn’t understand a word my cousins were saying to me at our first family reunion celebrating our homecoming. I started school that same Fall, I still couldn’t speak English very well. It soon came back to me with the help of my very patient teacher, Mrs. Repath.”

Greta had a dream to return to Marstrand one day. However raising 4 children, working and dealing with the day to day that stretched into years and decades, that dream was always elusive.

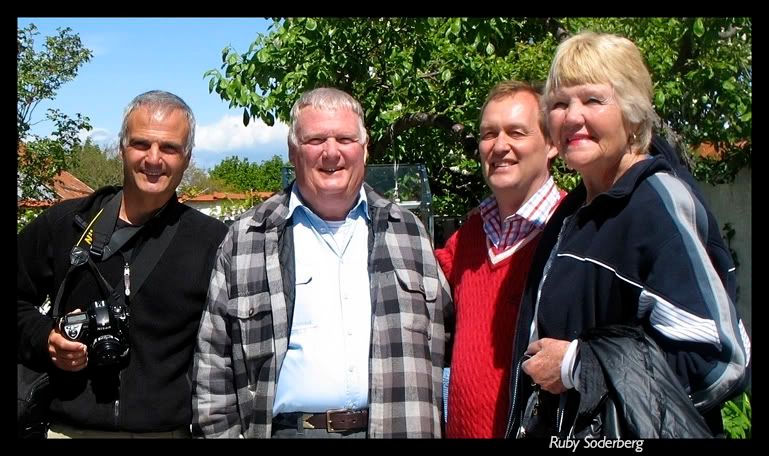

In 2005 Greta proposed the idea of going to Sweden and Marstrand to her nephews, Sam and myself–sons of Bill, Greta’s older brother. In May and June of 2006 we made that trip.

Next–Marstrand Return and Reunion.

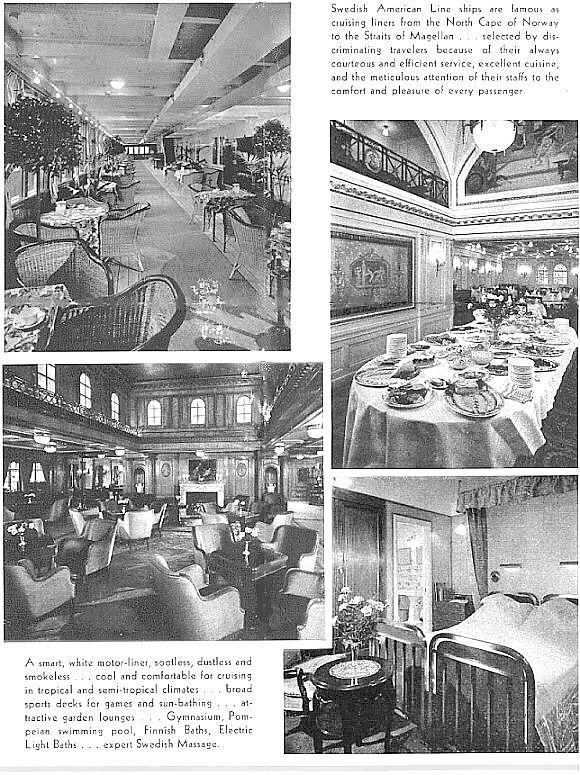

Gripsholm lifeboat drill.

Gripsholm lifeboat drill.

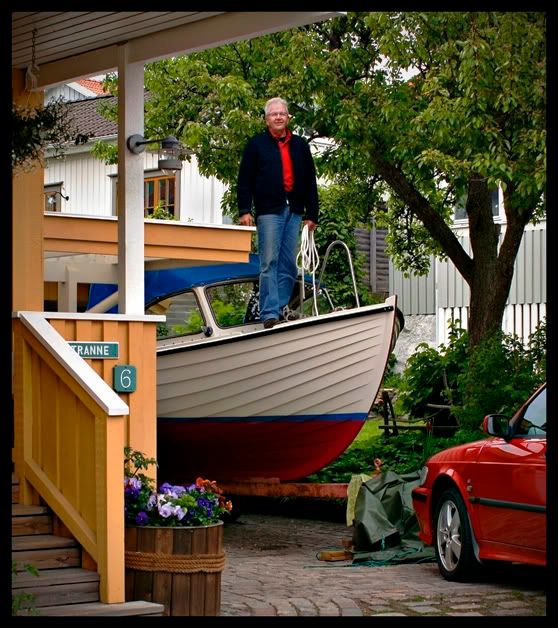

Gripsholm Skipper

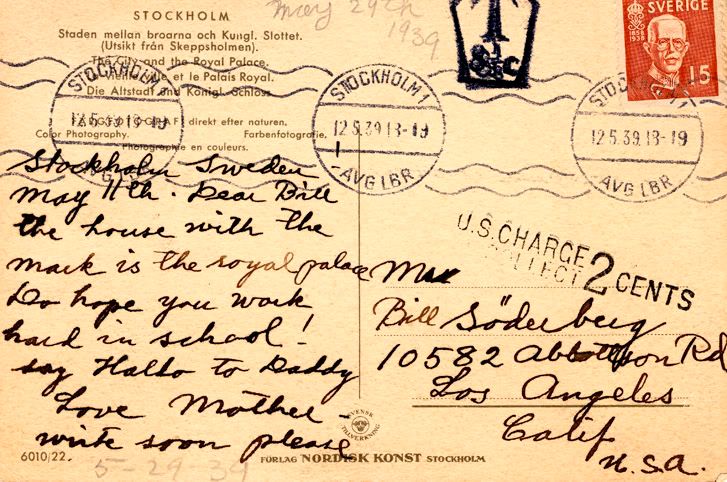

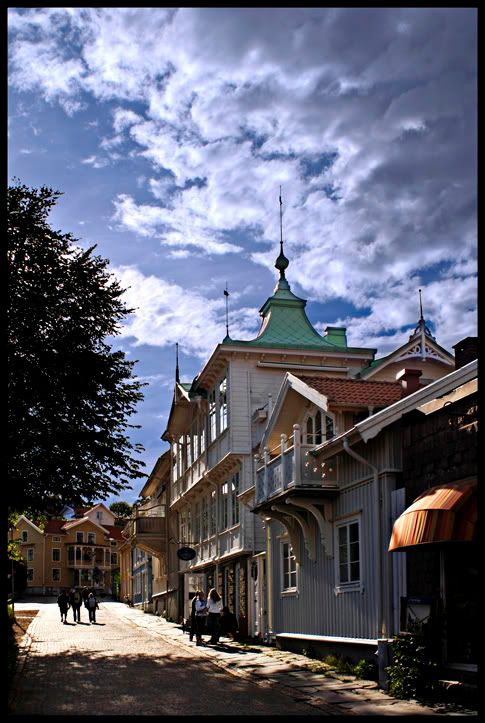

Gripsholm Skipper Marstrand, 1938 Postcard

Marstrand, 1938 Postcard “Uncle Algot”

“Uncle Algot”