Marstrand 11, Return and Reunion.

Marstrand, Sweden: My Family Story.

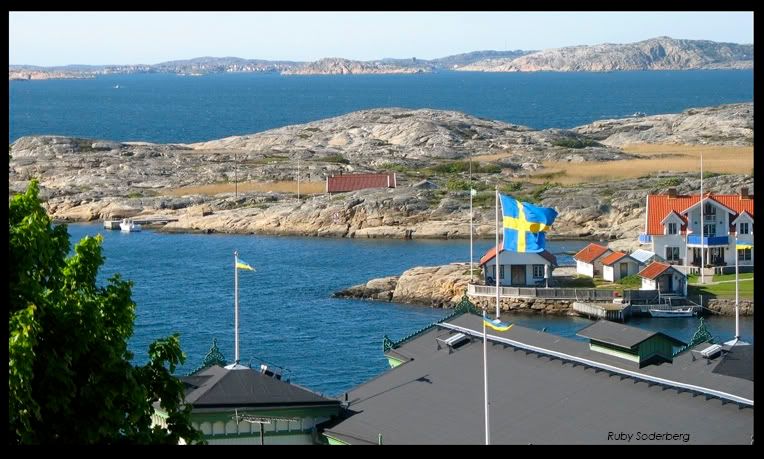

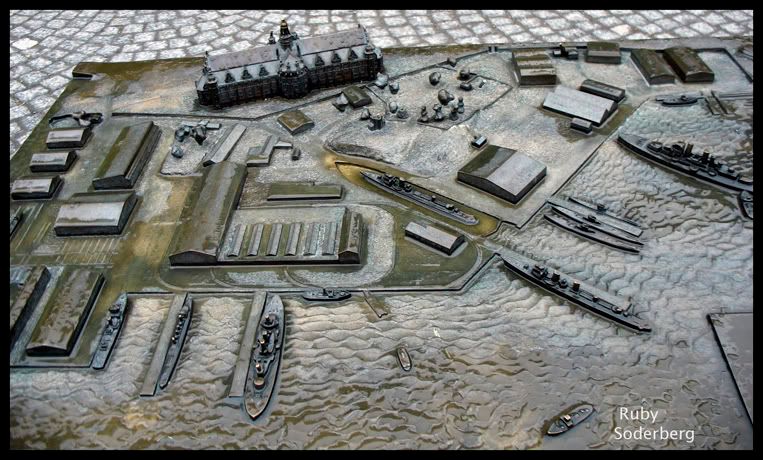

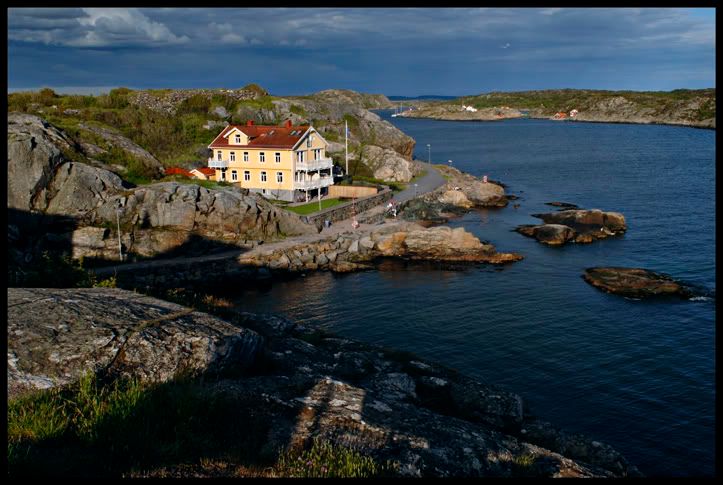

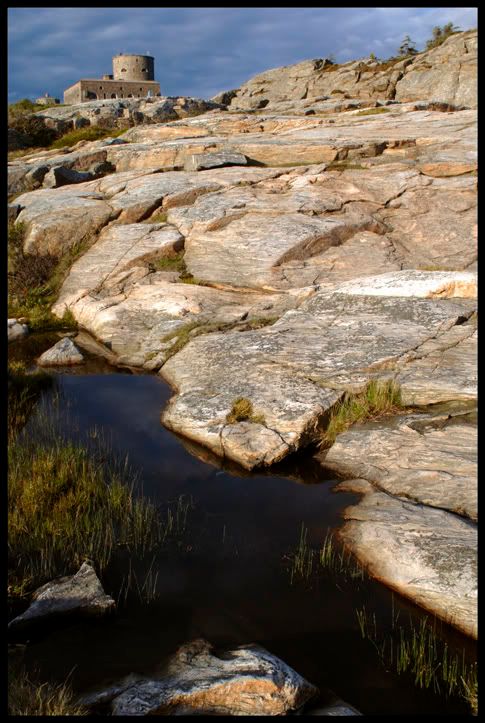

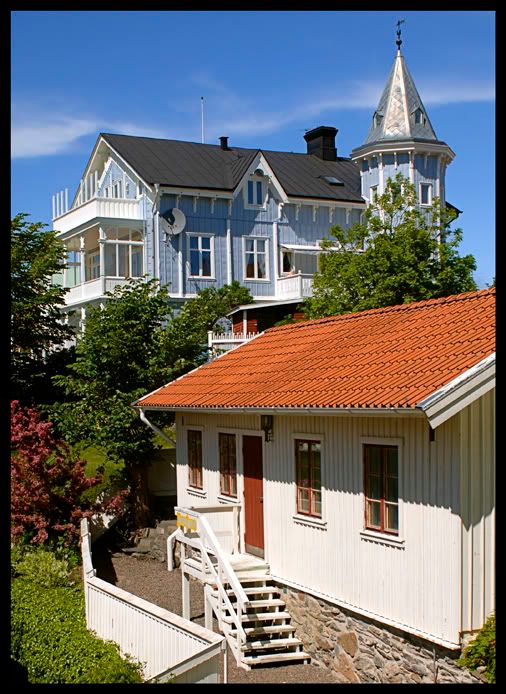

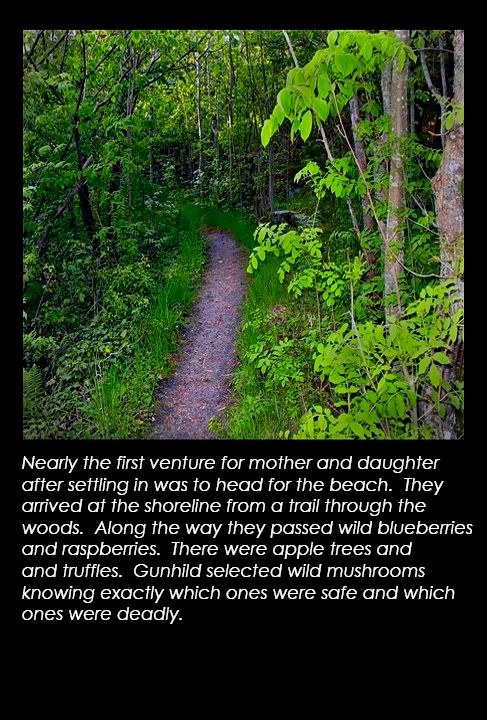

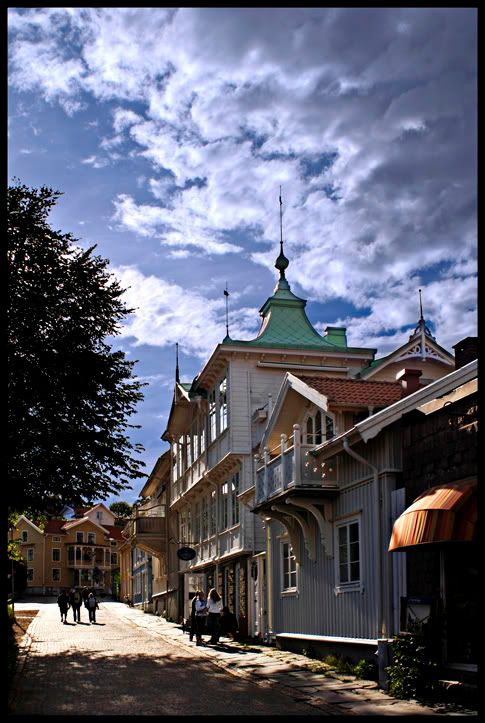

June 2006. Greta immediately recognized the rocky geography. Her bus window view was from the road between Göteborg and Marstrand. A road that was still under construction during her first trip to Marstrand. Her arrival then was by ferry. With the familiar silhouette of Carlstens Fortress on the horizon Greta was nearly “home.” Once upon the cobblestone streets, there was no hesitation about the familiar way to the old house of August and Alma Palm. Stepping to the veranda she pointed to a window. A room where the Christmas tree once stood. She remembered the rustic kitchen and the relic of a stove her mother created meals upon. She looked out from the veranda on a peaceful Marstrand harbor and remembered fishing with Grandfather August. She recalled the sight of ships at battle.

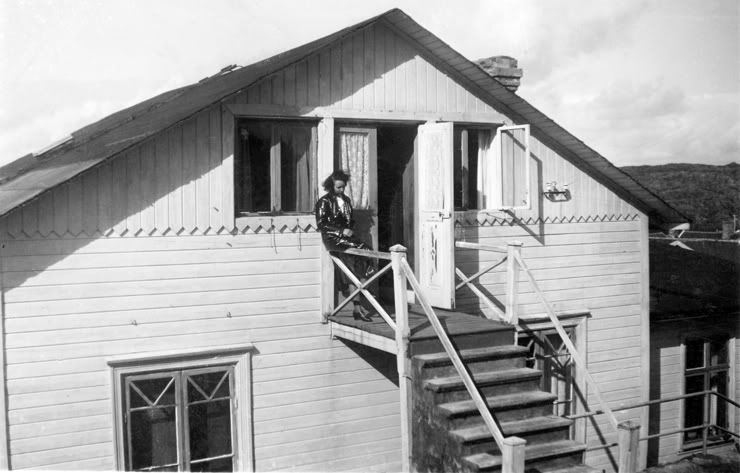

Greta on the veranda, 2006 (left). On the veranda 1939 (right). From right to left, Greta, Gunnar, Gunhild, & friend.

Question remained if she would find anyone she remembered. Or if anyone was still around that remembered her, her mother and grandparents. Or if there was even a chance of finding relatives.

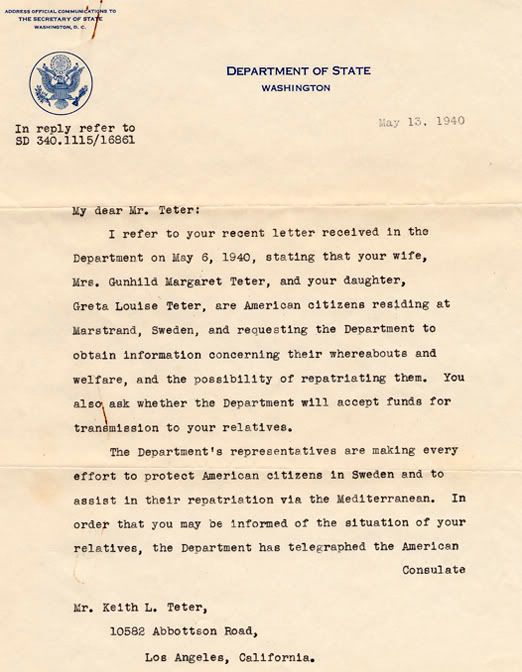

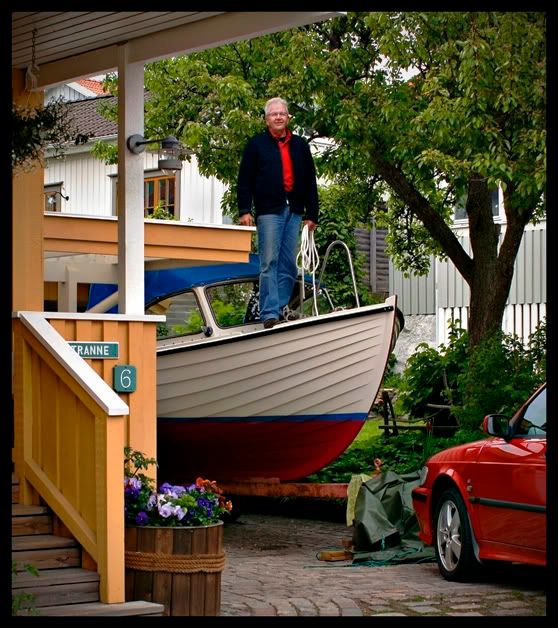

Our Innkeepers were Lena and Gunnar Danielsson at Korsgatan 5 in Marstrand. When they heard Greta’s story, they were very interested and became actively involved. After a few phone calls they offered Greta a pleasant surprise.

Lena Danielsson located one of Greta’s old Marstrand friends Karin. Lena invited Karin to Korsgatan 5 for coffee and coffee bread. Karin remembered the “American girl was allowed to have painted nails.” Sam Soderberg, center.

More surprises were in store. The next came via a short boat ride.

It is about right to say the Marstrand experience is incomplete without a boat ride, not counting the ferry. Gunnar Danielsson at the helm. Lena Danielsson at the rope. Sam Soderberg with floppy hat. Greta. And Sam’s wife Ruby.

Walking down memory lane, Greta meets with Ingrid, her second rediscovered friend.

A reunion sixty six years in the making. Ingrid, Greta, and Karin.

There were more happy meetings for Greta behind this door.

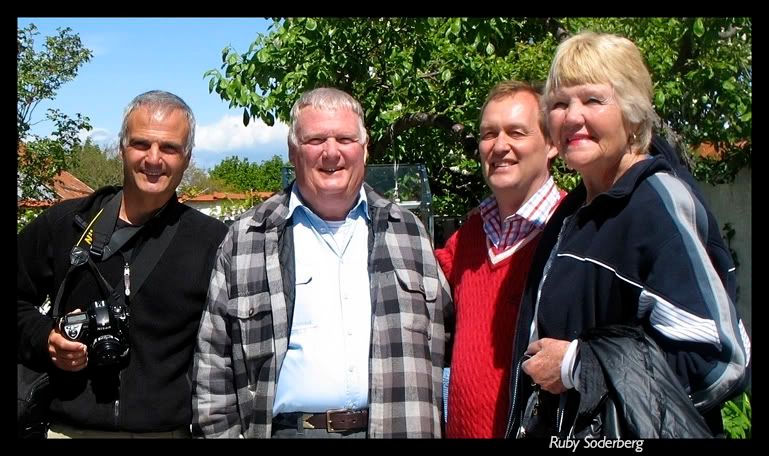

Dan and Sam with Swedish third cousin Anke, Greta’s second cousin. The three third cousins share the same great grandparents, August and Alma Palm. Anke’s grandmother is Margit, Gunhild’s sister. This is at the patio area of Anke’s home in Marstrand. He operates an antique business in Göteborg.

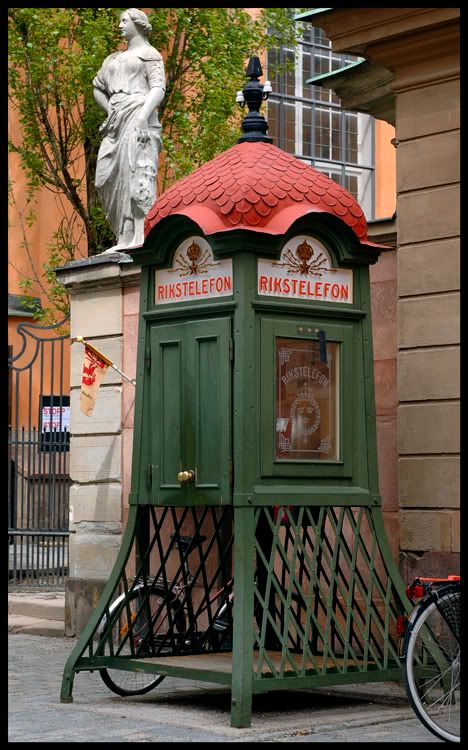

Ingrid, center, is a curator at Marstrand’s History Museum. She opened the doors for us. We studied the displays and learned from her expertise. Greta, and Gunnar Danielsson look on as Ruby asks questions.

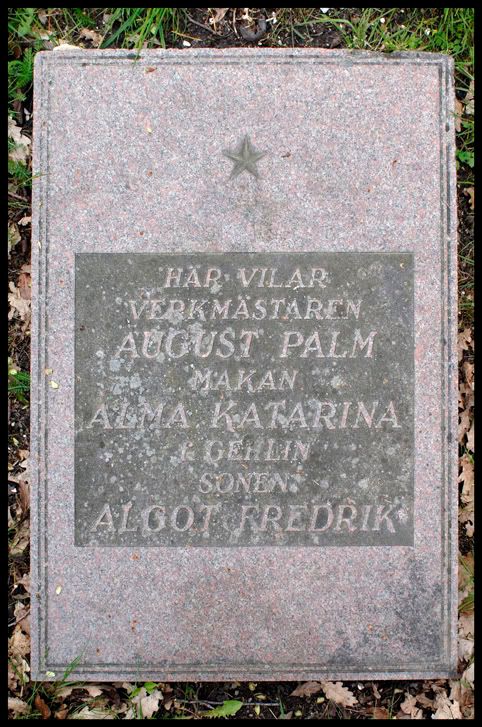

Another priority of our Marstrand stay was to locate the grave site of August, Alma and Algot Fredrik.

We walked and walked through the small cemetery in search of the family grave marker. It seemed every stone was looked at repeatedly. No matter how often the same markers came into view, the names August, Alma Katarina Palm, and Algot Fredrik were not there. A pile of discarded grave stones were set to the side. We happened to see the Marstrand Lutheran Church Vicar nearby attending to a site. He couldn’t recall ever seeing the name Palm. Then explained unmaintained or abandoned sites are made available as new plots. “Space is limited here.” The old stones are set aside or carved over to mark more recent burials.

From nearby trees the “cuckoo” of cuckoo birds seemed to herald our departure and unsuccessful quest. We were just past the cemetery gates when a woman called out.

“Did you say you were looking for August Palm? It’s right here.”

One sensed Greta’s relief. I imagined the trip would have felt somewhat incomplete if the grave site had not been found.

Perhaps we didn’t look as closely for a horizontal or flat gravestone. Most were the upright markers.

We made a second visit later. Greta bought some petite roses to plant at the site. “Mama would want that.”

Sam adding a cup of water to Greta’s freshly planted roses.

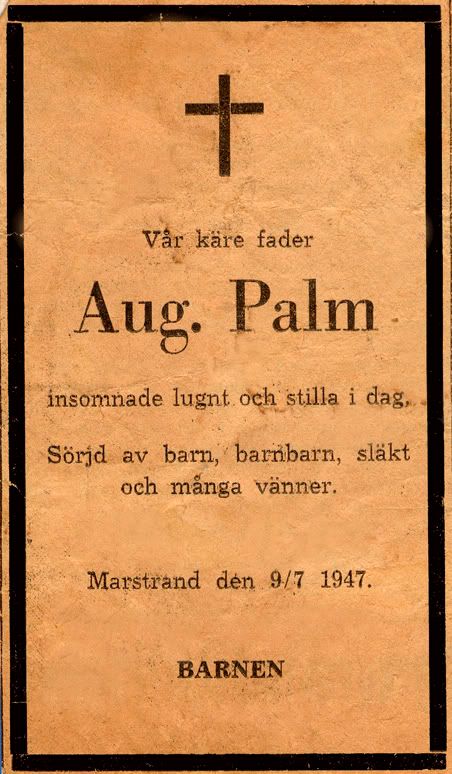

August passed away in 1947

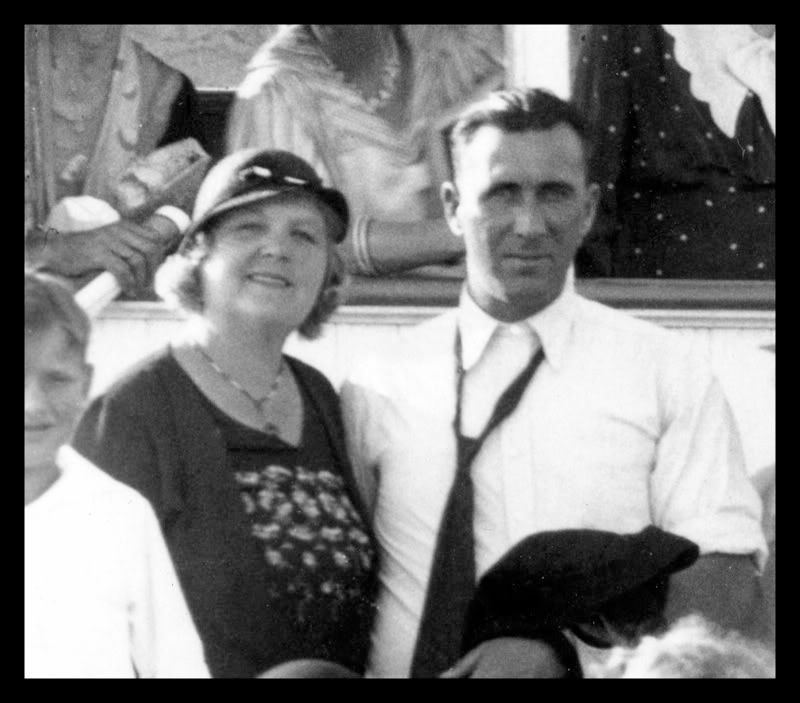

Grave yard service for August. We noted the flowers tied together with U.S. Flag ribbon. We imagine Gunhild sent those.

The Watch and The Broach.

“It was on a lazy afternoon in the summer of 1939. Mama’s work was done at the house and we went swimming. I swam and played for several hours when she decided I should come out and rest a bit. While Mama dozed in the sun I explored the rocks and crevices. Deep in one of those crevices I saw something shiny. It was very far down and I had to lie on the rock very flat. I reached my arm down and stretched as far as I could. I barely managed to touch it with the tip of my fingers. I couldn’t quite pick it up. I held my breath, lunged as far as I could, and managed finally to lift the object between my outstretched fingers. Gingerly, carefully, I pulled the object up against the rough rock surface. To my surprise it was a beautiful gold watch. I ran to my mother holding out my treasure.”

Gunhild was even more surprised because she recognized the watch.

“‘I know whose watch that is, Greta. We must find Mrs. Ambjornson and return it. She will be very sad when she realizes she has lost it.'”

Mrs. Ambjornson in fact had tears upon seeing it. “My husband gave this watch to me on our wedding day. I have always cherished it and now he is gone.” He drowned a few years ago when a storm caught hold of his sail boat. “It is the most precious memory I have of him. It is worth more than money to me.”

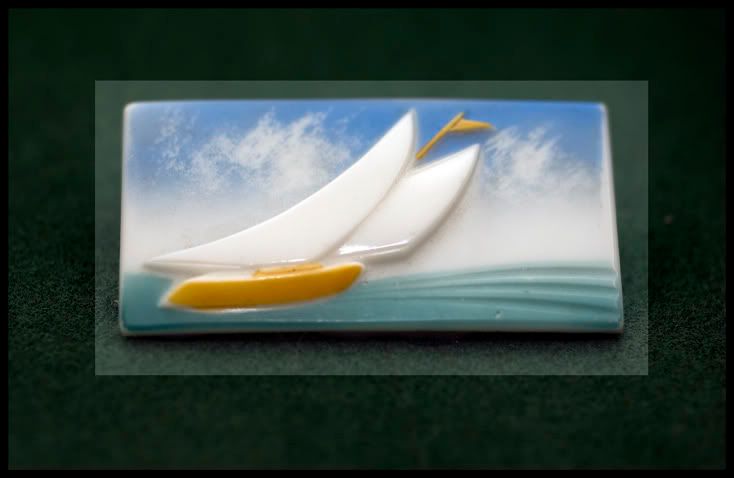

Mrs. Ambjornson rewarded Greta with a trip to a jewelry store. Greta chose a simple porcelain brooch with a carved picture of blue water, blue sky with white fluffy clouds, and a sail boat on it.

“To me this was Marstrand. The water I loved to swim and sail upon. The open sea and the wind blowing through my hair. With this pin I always remember the best things I love about Marstrand and how it was.”

“Under Mama’s protection my childhood cares were few. Life was a party; a new and exciting experience every day. I greeted each new day with excited anticipation.”

The End.

acknowledgment

Greta Louise Teter Smith for unrestricted access to her personal history on Marstrand and to Gunhild’s letters. Also for opening the family photo album and answering a myriad of questions over the past few years.

Ruby Soderberg, additional photography

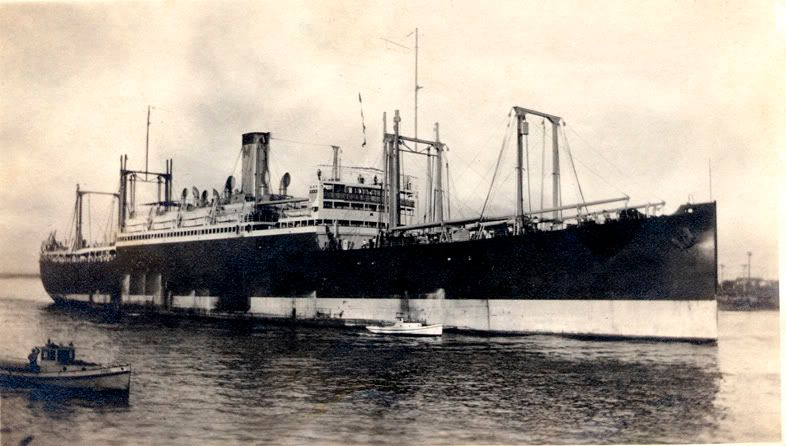

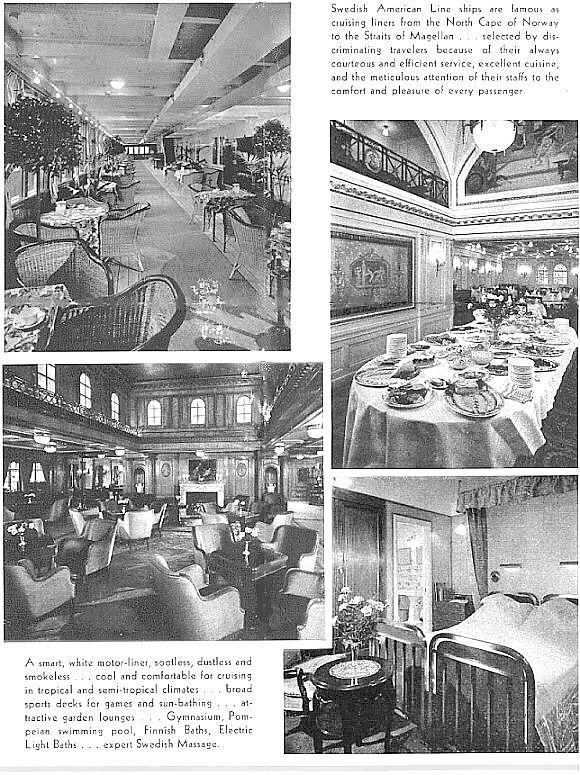

Mark Wagner, permission to use images of The Gripsholm

Gunnar and Lena Danielsson, for all their help not only in providing a top notch Bed and Breakfast Inn in Marstrand, but for all the attention given to making Greta’s return so memorable.

Korsgatan 5 SE 44030 Marstrand, Sweden. Tel +46 (0)303-14827 Fax +46 (0) 303-64807

Gripsholm lifeboat drill.

Gripsholm lifeboat drill.

Gripsholm Skipper

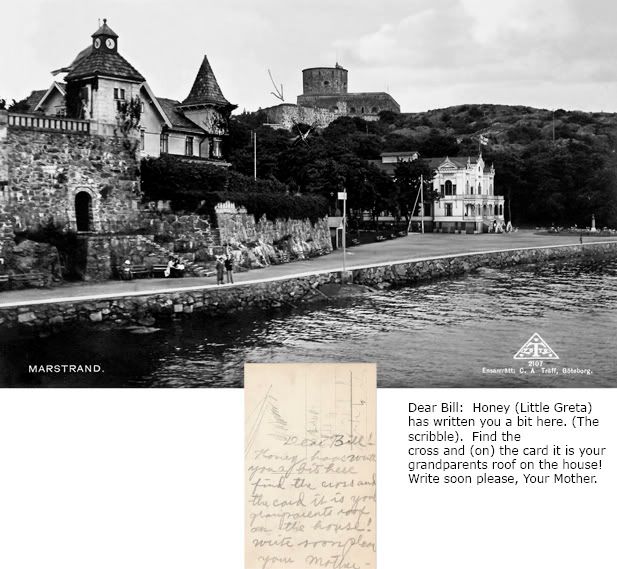

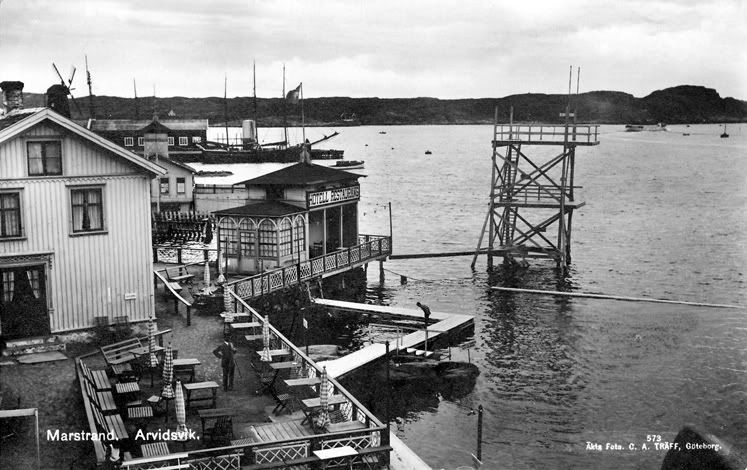

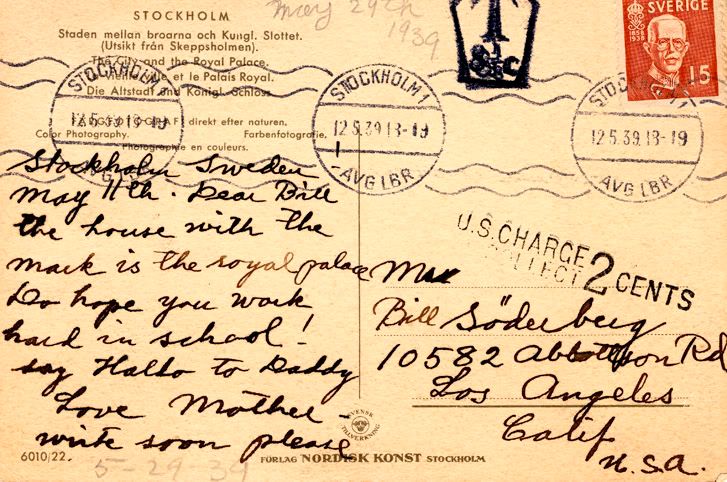

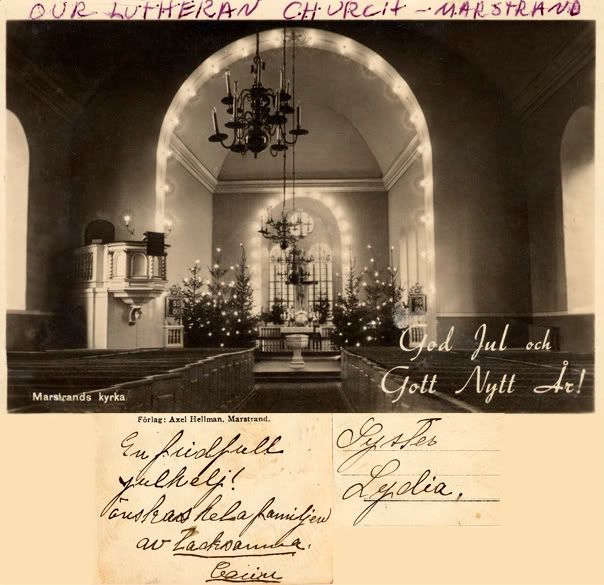

Gripsholm Skipper Marstrand, 1938 Postcard

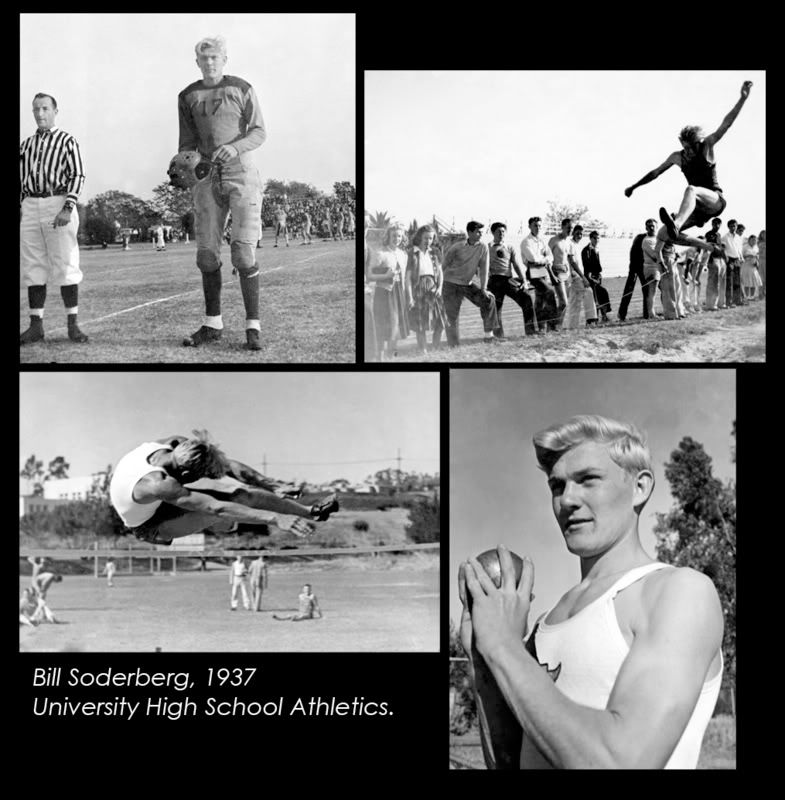

Marstrand, 1938 Postcard “Uncle Algot”

“Uncle Algot”